The I in ACID stands for isolation. It guarantees that all transactions occur in isolation and that one transaction cannot affect another transaction in any way. But the reality is that most databases do not support this out of the box. There are various weak isolation levels that provide isolation to some extent.

The literature on this topic available on the internet is often misleading. This is because they tend to omit information or rely on old incomplete SQL standards.

To first understand isolation levels, we need to understand what kind of concurrency bugs are possible. These are called “phenomena” in the SQL Standard. But since it’s widespread, better to use the same jargon for shared understanding.

Phenomena

1. Dirty Reads

When one transaction reads uncommitted values from another transaction.

2. Non Repeatable Reads

When a transaction reads a row at one point in time and then later reads the same row, but finds that it has been updated (by another transaction). Note that this row update has been committed by the other transaction, so it’s not dirty.

3. Phantom Reads

When a transaction retrieves a set of rows based on where clauses. but when it runs the query again, it gets a different set of results. This happens because another transaction might have a) inserted a row that matches the where clause. b) deleted a row that matched the where clause. c) updated the value of a row such that it no longer satisfies the where clause.

It’s called phantom because the rows were there for a moment, but not there again later. Think “illusory”.

Note: It’s important to understand the difference between Non Repeatable Reads and Phantom Reads. At first glance, both might seem similar, because both depend on reading something and reading it again and finding it changed. But, they are different because Non Repeatable Reads correspond to single rows being updated, while Phantom Reads is about finding that the set of rows changed (due to inserts, deletes, or updates).

4. Serialization Anomaly

This is an ambiguous term that’s only mentioned in a few places. Particularly, the Postgres documentation defines it as “The result of successfully committing a group of transactions is inconsistent with all possible orderings of running those transactions one at a time”.

It means that if we run a set of transactions in all possible orders, we would expect the same consistent result every single time. But if one order results in a different result compared to another order, it means that we have an anomaly (serialization anomaly).

So, it’s essentially a catch-all term that’s supposed to represent every other concurrency bug that’s not covered in 1, 2, and 3. The following are some of the concurrency bugs/phenomena possible in this category.

-

Lost Updates

If a transaction (tx1) reads a value, modifies it based on a condition and writes it. It’s possible that another transaction (tx2) at the same time reads the value, modifies it based on a condition, and writes it. But only one write would be possible, usually the last write (last write wins strategy). This is a problem in certain scenarios. For example, consider 2 clients trying to increment a value. tx1 reads the value (a), increments it (a+1), and tries to update the row. Simultaneously tx2 also reads the value as a and increments it. The expected final output is a+2, but in reality, it’s a+1, because only one write won. This happened because each transaction can only read committed values.

-

Phantom Writes

This is quite similar to the above situation, except it generalizes to a set of rows under a search condition. tx1 and tx2 modify a set of rows under a search condition, which is no longer valid or applicable by the end of their respective executions.

-

More scenarios are mentioned here [1] along with the corresponding source literature.

Confusion 1

1, 2, and 3 are mentioned everywhere online. e.g GeeksForGeeks has an article here [3] too. These articles are quite misleading as they omit crucial information for understanding transaction isolation levels. The GeeksForGeeks article doesn’t mention any other kind of phenomenon, which is unfortunate because it’s one of the most popular websites for learning computer science concepts.

The Postgres documentation [2] on this topic does a better job by including 4 as well. Though it still uses Serialization Anomaly has a catch-all phenomenon for all possible concurrency bugs.

Unfortunately, the confusion doesn’t stop here, as we will see below.

Transaction Isolation Levels

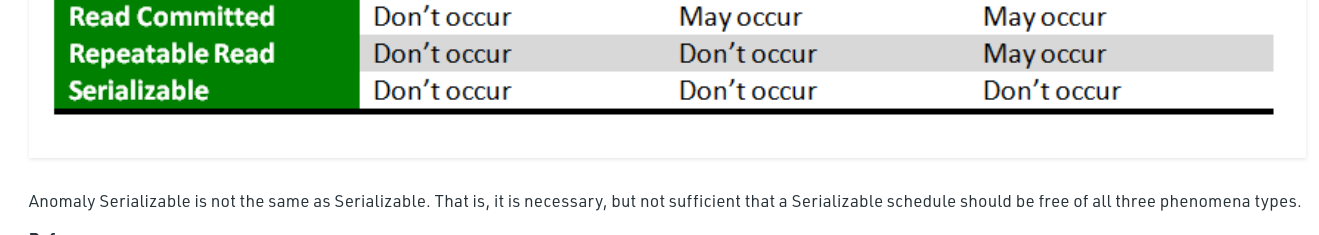

Based on phenomena 1, 2, and 3, the SQL standard declared 4 isolation levels. Databases can implement support for these levels and claim to be compliant with the SQL standard.

1. Read Uncommitted

This is basically the wild west when it comes to isolation. Anything goes, zero isolation. Transactions can read each other’s uncommitted data and overwrite it whenever.

2. Read Committed

Here, a transaction can only read committed data from another transaction.

3. Repeatable Read

Here, a transaction can read the same row multiple times and get the same data, even if the actual row was modified by another transaction. This means that the transaction could be reading a stale copy of the data.

But, this does not necessarily preclude the possibility of Phantom Reads. Repeatable Read is about a specific set of rows, but not about a set of rows under a search condition.

Confusion 2

This is another confusing aspect about isolation levels as the name “Repeatable Read” seems like it should also prevent Phantom Reads, but according to the ANSI SQL standard, it doesn’t [4].

To add to that confusion, both Postgres and MySQL prevent Phantom Reads as part of the Repeatable Read isolation level, so their version of Repeatable Read is closer to Serializable than the ANSI SQL Repeatable Read [2]. Additionally, Postgres’ Repeatable Read prevents Lost Updates, but MySQL Does not [2,5].

4. Serializable

This is the ultimate isolation level and represents the I in ACID completely. Transactions are serializable if they can be ordered in any way and produce the same result. Concurrency bugs should not be possible at this isolation level.

Confusion 3

Regarding isolation levels, once again GeeksForGeeks gets it wrong.

-

It mentions that Repeatable Read is the “most restrictive” isolation level, but also says that Serializable is the “highest” isolation level. They never explain the difference between “most restrictive” and “highest” isolation levels.

-

At the bottom it brings up “Anomaly serializable”, but it’s never been defined before in the article. Turns out that it was copied directly from the Wikipedia article, which itself was poorly written (at the time of writing). But, at least the wiki article properly links the source paper for further clarification.

Conclusion

There are 3 main takeaways:

-

Phenomena are poorly defined and usually incomplete, even on popular websites. If you’re reading literature on the topic, make sure to check if the article acknowledges concurrency bugs beyond those that are read related.

-

Isolation levels are also poorly defined by the initial SQL standard and everyone interprets it however they want. If you’re reading literature on the topic, make sure to check if it acknowledges the difference between the SQL standard and modern interpretations.

-

The implementation of these isolation levels also varies significantly across databases (even the popular and widely used ones). Postgres and MySQL provide Repeatable Read by default but it behaves differently in each. Make sure to verify your understanding by reading the respective databases’ documentation.

References

- [0] https://martin.kleppmann.com/2014/11/25/hermitage-testing-the-i-in-acid.html

- [1] https://github.com/ept/hermitage#summary-of-test-results

- [2] https://www.postgresql.org/docs/14/transaction-iso.html

- [3] https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/transaction-isolation-levels-dbms/

- [4] https://medium.com/db-journal/repeatable-read-is-not-repeatable-c700b2ce1c76

- [5] https://dev.mysql.com/doc/refman/8.0/en/innodb-transaction-isolation-levels.html